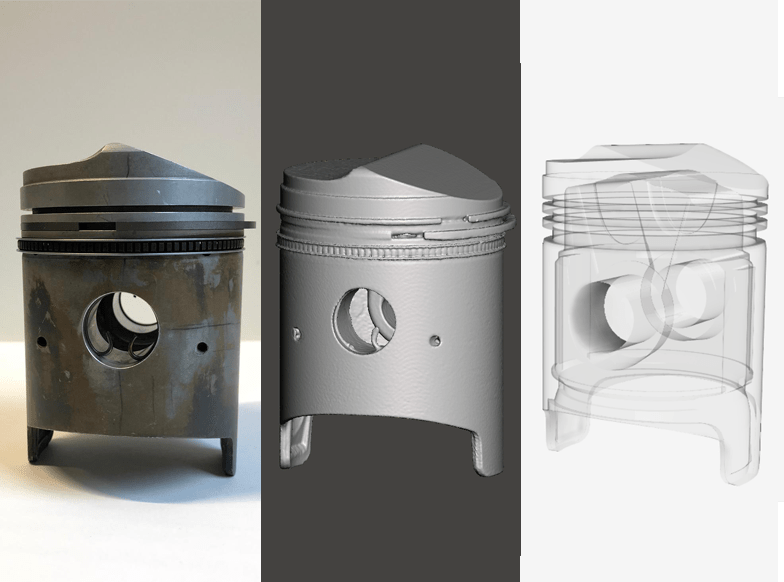

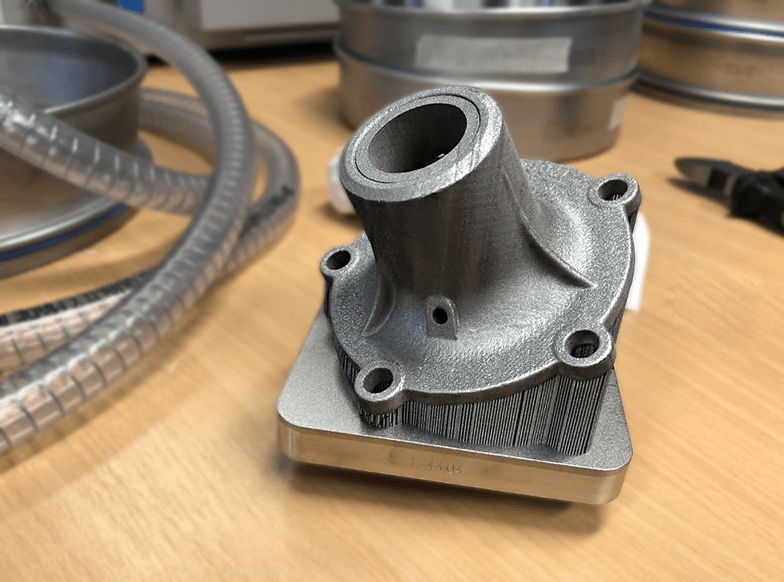

Developing a 3D repair cycle in which old or broken parts are scanned or measured, digitally repaired, 3D-printed and reworked, until they are ready for use.

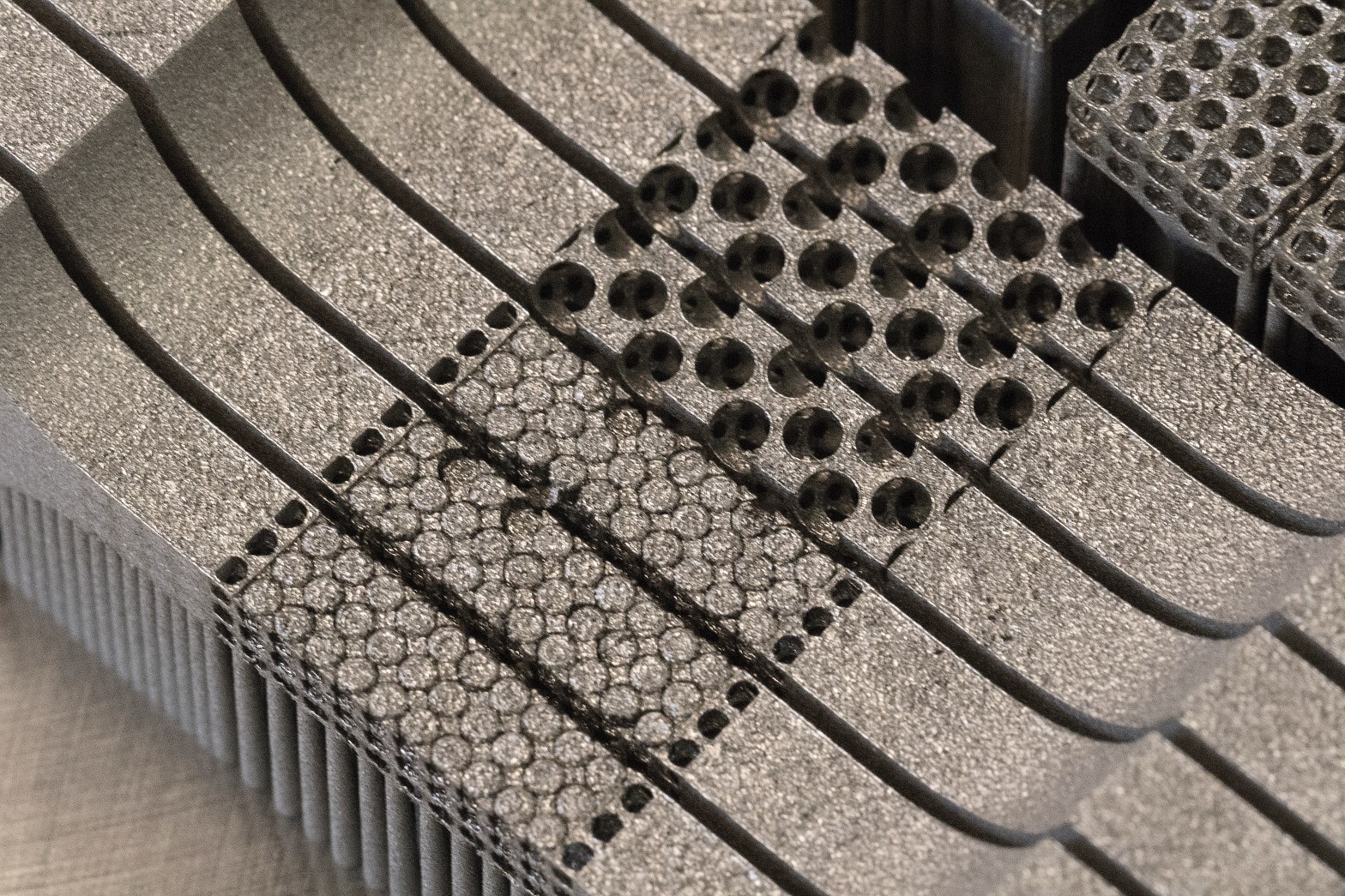

3D printing technology (Additive Manufacturing, AM for short) has undergone strong development over the past 10 years, with special applications. Plastic is a well-known 3D printing material, and new types of materials such as metal, sand and even organic material are constantly being added. Advantages of opting for a 3D printing technique are, for example, freedom of form, function integration and material / waste reduction.

At Saxion, on the basis of two TFF projects, 3D Metaalprint-Biz1 & Biz2, in collaboration with a number of partners from the industry, knowledge was gained about (re) designing and producing in the field of 3D metal printing. Many students in the form of multidisciplinary project groups, interns and graduates were involved, who, together with lecturers and researchers, derive design and production guidelines based on cases.

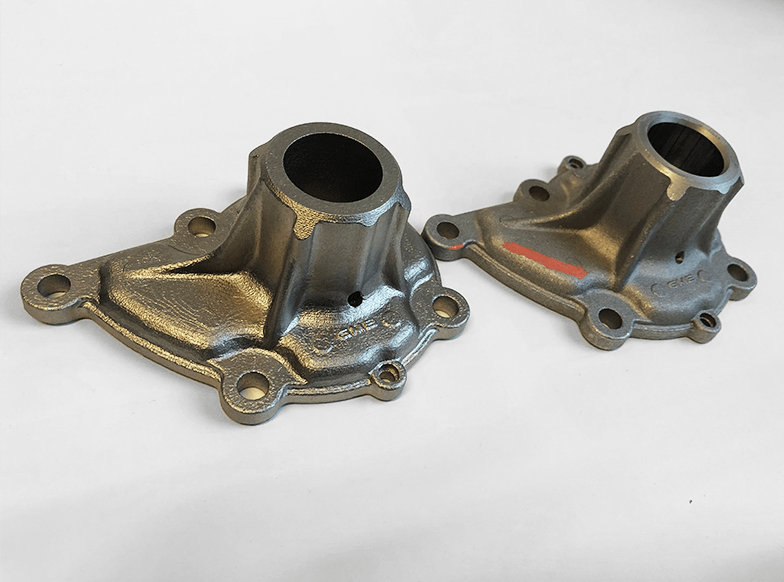

With the knowledge already acquired about 3D metal printing as a starting point, we now want to investigate whether it is possible to reproduce or repair existing parts. While in 3D metal printing at the moment people prefer to use the possibility to optimize parts as much as possible, in this project it is precisely the idea to copy the products as well as possible (acceptable to the customer). The function of the part remains the same and the appearance must look the same, or at least be perceived as such. However, in order to be able to 3D print, a number of concessions will be necessary, this entails a field of tension that requires research into how many concessions are possible.

Spare parts are already being 3D-printed in various industries. A good example are spare parts that Shell prints specifically for oil drilling platforms. A consideration of Shell not to (completely) redesign the parts is that they must be implemented in an existing setting, since the spare part is part of an existing setup. Furthermore, the supplier is often difficult to trace due to the antiquity of the drilling platforms. By printing the spare part, Shell saves a lot of time on research and delivery times, making the platform operational faster. This is of great value when every non-operational day of the platform costs almost 1 million euros.

When looking specifically at the intended cases within this project, Oyfo is faced with the impossibility of producing the parts of the museum pieces (just being museum pieces implies the scarcity). Of the cast iron pieces, which are often 100 years old or older, no more casting molds can be found. How should the part be repaired or manufactured? Additive Manufacturing can be a huge solution here. For MRM the same problem occurs in another sector, some parts are so scarce that they are either unavailable or the price is too high.

There is a lot to do in the field of printing spare parts and so-called smart warehouse / factors. At the University of Paderborn, a technology has been developed with which (broken) parts that have been scanned can be repaired with the help of software. However, the original CAD drawings are still required for comparison.

The real question, however, is what if the part is no longer available, is no longer made or if there are not even any drawings left? What if there is only the broken part? Old steam engines, that oldtimer, that one loom or a part from a forgotten lock or windmill that suddenly breaks down, what next? The solution is devised for that question in this project.

Duration: 2019 – 2020